I came across the work of the writer Ronald Duncan when I was staying at the Old Vicarage in Morwenstow, during September 2010 (see my previous posts, Ronald Duncan at West Mill and Marsland Valley). I was researching the life of the poet, priest and antiquary, Robert Stephen Hawker, and was intrigued to learn from a local map that Hawker’s own clifftop hut at Morwenstow was echoed by another just a few miles north along the coast. Duncan spent much of his time here, especially during the summer months, and composed most of his epic poem, ‘Man’, in these wild surroundings.

I was lucky to have a sunny morning when I followed in his footsteps along the track from Mead out to the cliffs, but the wind was fierce enough to cut right through my warm clothes and I found it hard to imagine making the trip day after day as he did. He constructed his original hut in the early 1960s but it fell into disrepair after his death in 1982. The rebuilding of the present hut was organised by his daughter Briony Lawson and local builder Tim Neville and the result looks sturdy enough to provide shelter for walkers for many years to come.

In the third part of his autobiography, Obsessed, Duncan describes how he came to acquire his refuge:

‘During the war, the Admiralty had asked my permission to erect a small look-out hut on the cliff edge above West Mill. It overlooked the approach to the Bristol channel. On a still summer evening in 1940 I had stood on that spot to watch eight ships in convoy blow up and sink within fifteen minutes. The hut the Admiralty erected was made of galvanised iron on a concrete base and measured ten by six feet.

After the war the Admiralty offered to take the hut away or let me have it as a gift. Since it was rusting and unsightly, I asked them to remove it. This they did.

A few years later, I found myself repeatedly going up the cliff path to sit for hours on this site. The view attracted me because it contained no signs of humanity: the open Atlantic, the bracken and gorse covered cliffs, giant boulders on the beach beneath. The only signs of life were the buzzards and a single unmated falcon. I was drawn to this view which had not changed since the Cambrian era.’

Obsessed by Ronald Duncan (p.105). Published by Michael Joseph, 1977.

Duncan became involved in a long battle with local planners, who first granted permission and then withdrew it, after stone, sand, water and cement had been laboriously carried by hand down to the the site and the walls had already reached a height of about three feet. Luckily for walkers on this stretch of the South West Coast path he finally won the day, the hut was completed and he was able to install his writing desk – a teak door from the Green Ranger, wrecked in the winter of 1962 on Gunpath Rock near Elmscott.

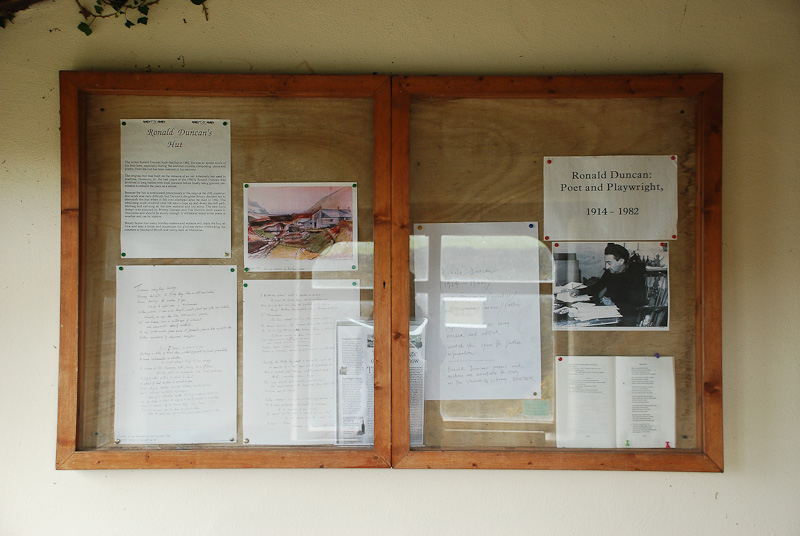

Today the hut is furnished with benches, as well as a table and chair and a visitor’s book full of appreciative entries from people who’ve taken a break here. Many of them are return visitors who know the history of the place, but for those who come across it unexpectedly the wall displays provide some background information. A box contains copies of Duncan’s books and a notice invites walkers to help themselves.

I’m not enthusiastic about heights, and the wind was fierce enough to make it difficult to hold the camera steady, but I managed to get a few exterior shots which didn’t involve standing too close to the 200-foot drop to the beach. There are a couple of braver pictures here, at The Solitary Walker’s blog.

I’d been hoping to do some writing of my own during the visit, but even inside the hut the noise of the wind was very loud, and along with the rhythm of the breaking waves it seemed to blank out my brain and banish any thoughts. After a while I did become a bit more comfortable with the openness and the sense of exposure, but it makes perfect sense to me that Ted Hughes once described his best ever writing space as the tiny windowless entrance hall in the first flat he and Sylvia Plath shared in London.

For Duncan the location obviously acted as an inspiration, and it crops up in his writing again and again. His long, five-part poem, Man, is far more abstract than his previous work – it opens with the origin of the solar system and explores the creation of life and the evolution of humanity – but his love of the place still shines through:

Then I sat down by that shore, the abyss above me

The unfathomable all about me. And I stared out at the sea

Realising: that I could not see the waves

Nor any part of the ocean

Independent of the process of observation;

that Laws of Nature were laws of thought,

And even Reason needs reason as method,

As the will, the will, before it can reason.

Then I peered out at the horizon

Where I myself sailed by oblivious to my signal,

And I stood up and shouted hysterically

Into the abyss before me, above me, and about me:

‘Order is what I seek.

From the chaos of my mind,

Order is what I will impose upon you.’

And the indifferent waves broke on the deserted shore

Echo alone answered. Then I wrapped that terror

which blew across the loom of space

closely about me like a scarf;

fear is not what I will fear,

it is indifference which frightens me.

Excerpt from ‘Canto Twelve, Kosmos’, from Man, Part One, by Ronald Duncan. Published by the Rebel Press, 1970.

Quotations from Man and Obsessed by Ronald Duncan, © The Ronald Duncan Literary Foundation. Reprinted by permission.

Other text and photos © Angela Williams, 2011

LINKS

Comments

3 responses to “Ronald Duncan’s Hut”

Dear Angela – Thank you for including this very special place on your blog. I hope that others will enjoy visiting the hut for many more decades.

Excellent work Angela; looks like an inspirational spot. Reminds me of Dylan Thomas’ hut in Laugharne which I visited recently.

[…] Soon after the border we found another hut, this time belonging to the poet Ronald Duncan. Not quite as tiny and hidden as Hawker’s, but with breathtaking views nonetheless. I know very little about Duncan, but on a subsequent search on his work and in particular on this hut, I found the quote below, which I think responds beautifully to the landscape it describes (thank you Literary Places): […]